Why must holy places be dark places?

I grew up with C. S. Lewis — or more specifically with The Chronicles of Narnia and The Space Trilogy. It was fun when the first and most famous Narnia story — The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe — was released as a theatrical film adaptation around Christmas 2005. And Lewis wrote a lot of other well-known fiction and non-fiction books on Christianity. I always saw the title Till We Have Faces in that standard “other works by author” page. It sounded like a weird and interesting name for a book. And just recently, I got around to reading the novel itself.

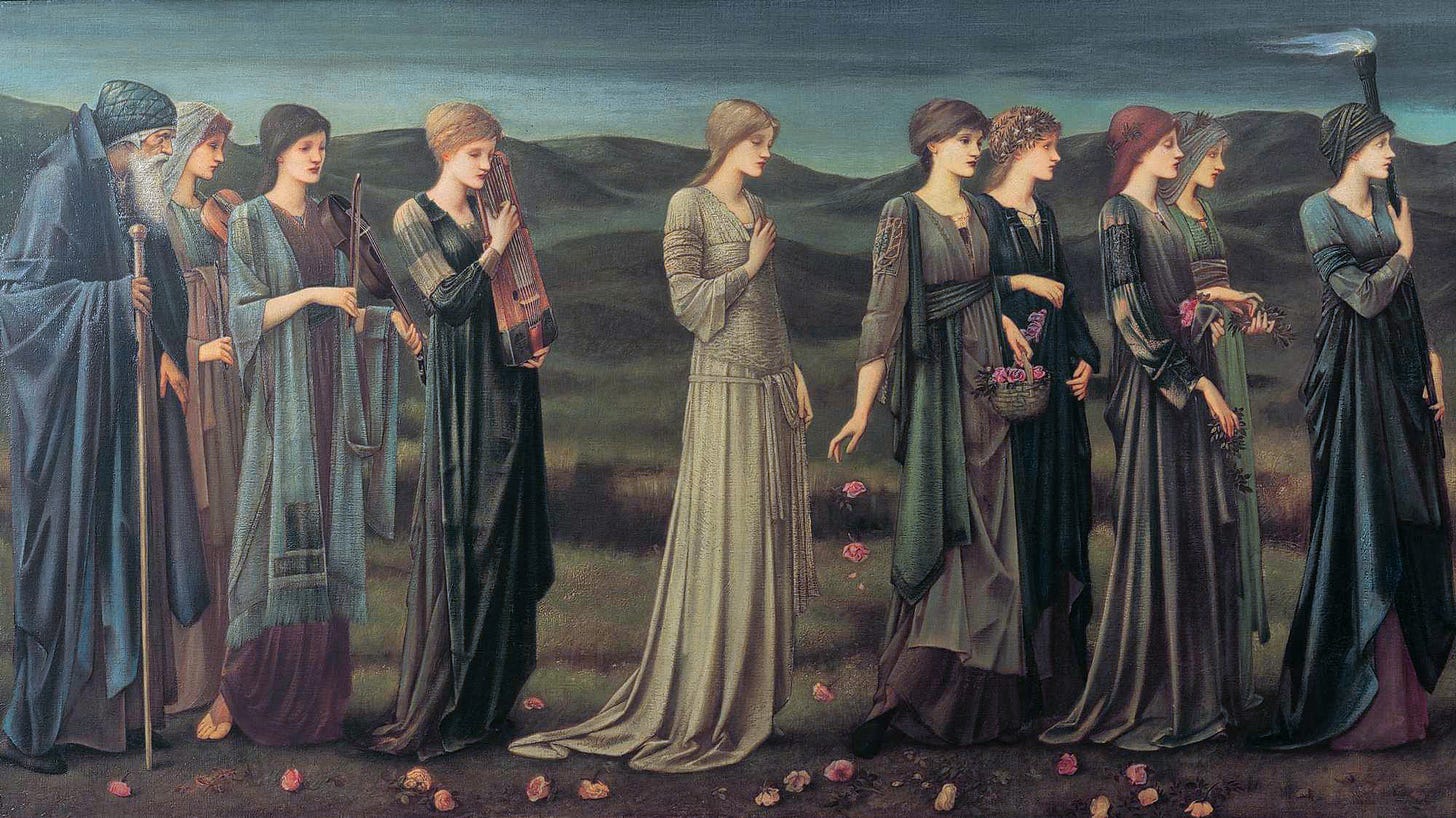

A student of myth, Clive Staples Lewis (1898-1963) was haunted by the Greek tale of Cupid and Psyche, thinking some of the characters’ actions didn’t make sense as described in the original. In this myth, written out by Apuleius in the 2nd Century A.D. but apparently predating him, Psyche is the youngest and most beautiful of three royal sisters — so beautiful that the people neglect their worship of Venus, who grows jealous. Venus’s own son, Cupid a.k.a. Eros, himself falls for Psyche and they get married after Psyche is walked out to an isolated location in what deliberately looks like a funeral procession.

The marriage actually works out well for Psyche, and she lives in splendor in the heavenly palace, even though her otherworldly husband refuses to show her his face. Psyche’s two sisters see how she lives, grow envious, and talk her into using a lamp to get a look at her sleeping monster husband. Of course, Cupid is gorgeous — but unfortunately for Psyche, he freaks out and leaves. Even as Psyche is wandering in search of her husband, her sisters are still envious. They end up lethally jumping off a cliff in attempt to get Cupid for themselves, prior to Psyche going through various ordeals and finally reuniting with her husband.

First published in 1956, Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold is based on the Cupid and Psyche story, and is said to have been co-written or at least influenced by Lewis’s wife Joy Davidman — though her exact degree of input is a matter of speculation. The novel changes some aspects of the original myth — primarily the role of the two elder sisters. They don’t die trying to play Jackass with the gods, and they are very different from each other — the middle sister ends up being a minor character, and it is only the eldest who talked Psyche into shoving a light at her monster-god-husband and may or may not be responsible for ruining Psyche’s life.

Orual is the name given to the eldest sister, and she is the protagonist and viewpoint character of Till We Have Faces. In Lewis’s novel, Orual is determined to tell her side of the story: her intentions were good, she’d been done dirty by the gods with their opaque ways, and she was not only going to set the record straight, but make her case against the gods themselves. Or... were her intentions good?

As with most of my reviews and analyses, full-plot spoilers are ahead.

The story takes place in the fictitious barbarian society of Glome. Orual is ugly in physical appearance, which her callous father King Trom won’t let her forget as he makes her stand in front of a mirror. Orual and her sister Redival are not particularly close, and as they get older, Orual considers Redival to be shallow and attention-seeking. Their mother dies when they are young children. The local barbarian religion is dark and weird. Their equivalent of Venus is named Ungit, and instead of a detailed statue, her representation is this uncannily smooth, pitch-black, oblong thing. C. S. Lewis gets the concept of “less is more” and “don’t show the monster.”

Then, Trom’s second wife also dies giving birth to the king’s third child. He is disappointed that the new baby is another girl, but the birth of her half-sister Istra (Psyche’s birth name in the book) is one of a couple bright things going for Orual’s life. The older girl looks after Istra, and with the age gap between them, the sisters’ relationship is often more like that of a mother and daughter.

The second thing young Orual has going for her is receiving an education with the arrival of The Fox, a.k.a. Lysias, an enslaved Hellenistic Greek scholar, who brings light and logic to Orual’s growing-up years. The princess takes to reason and philosophy as she prepares for leadership. Lysias is a wise and virtuous mentor, and undoubtedly a positive influence on her. Orual is understandably alienated from her own culture and religion, and the darkness itself is her blind spot — light and reason are not the only aspects of life.

Psyche, on the other hand, finds balance. She sees the value in The Fox’s enlightened stoicism, while also taking to the dark ritual religion of Glome.

Orual is devastated upon learning that Psyche is to be offered as a human sacrifice to Ungit’s son, the God of the Mountain. And when Psyche is alive and happy to be married to the unseen god, and finding where she really belongs, and living in an invisible palace, Orual rationalizes that Psyche is hallucinating and being scammed somehow.

Orual threatens to stab herself, emotionally blackmailing Psyche into betraying her mysterious husband by sneaking in a lamp at night. (The God of the Mountain, or what little is seen of him, is dark and serious and not at all like the Cupid of Greek myth, who was more like a mischievous romcom playboy — I mean, obviously — who found the one woman he wanted to commit to.) Psyche and the God of the Mountain are separated from each other — implied to be on account of Ungit — and Psyche wanders alone.

Orual blames the gods for her role in the whole thing, claiming she never would have done what she did to her younger sister if the castle had been obvious to human eyes. How was it fair for the gods to be so elusive, and then allow humans to take the fall for the consequences of divine elusiveness?

Even as she is brooding on her case against the gods, Orual moves on with her life. She veils her face, which eventually makes herself appear fearsome and mysterious. Bardia, a military officer of Glome, has already taken notice of Orual’s potential skill for battle, and trains her as a warrior. Over the years, Orual accomplishes a lot, takes on an active advisory role, introduces books to Glome, and eventually becomes the queen of Glome. In her contact with neighboring lands, she is salty to learn the well-known version of the Cupid and Psyche story where she has been turned into a caricature of petty envy. Who, me? Orual wants to prove that her intentions were good, and came from a place of concern for her sister’s well-being, and it was not her fault that Psyche’s life was ruined.

As an old woman, she finally, finally gets a chance to read her case to the gods — even if it is only within a dream or vision. She takes the podium, and instead of reading the rational and methodical account she had planned to present, she ends up spilling her true subconscious inner thoughts — going on an unhinged rant about how she had given everything to Psyche, and then the gods took Psyche, and Psyche got to be happy without her, and that was terrible. So… petty envy was actually kinda right. The entire time, Orual had lacked self-awareness into her own “devouring mother” side, her shadow side.

“The complaint was the answer. To have heard myself making it was to be answered. Lightly men talk of saying what they mean. … I saw well why the gods do not speak to us openly, nor let us answer. Till that word can be dug out of us, why should they hear the babble that we think we mean? How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?”

From C.S. Lewis’s Christian viewpoint, it’s not that God is elusive and mysterious to humans simply to toy with them. It’s that humans lack self-awareness, and the distance between themselves and God is rather self-imposed.

So, Orual has a rough “I’m the bad guy?” moment. She looks at her life in a different light — she had ulterior motives for making Bardia work late, she should have given Lysias his freedom to return to Greece long ago, she had abandoned and misjudged her other sister Redival.

And yet, no one is all good or all bad. Orual is neither a flawless girlboss role model, nor did having an unexamined shadow side cancel out all the good she did. In the balance, when she dies, Orual is remembered as a great and accomplished leader to her people: “the most wise, just, valiant, fortunate, and merciful of all the princes known in this part of the world.”

I read that book way back in 2007! It sticks with you even if it isn't the most exciting. Lots of memorable imagery, and even the title is unforgettable.